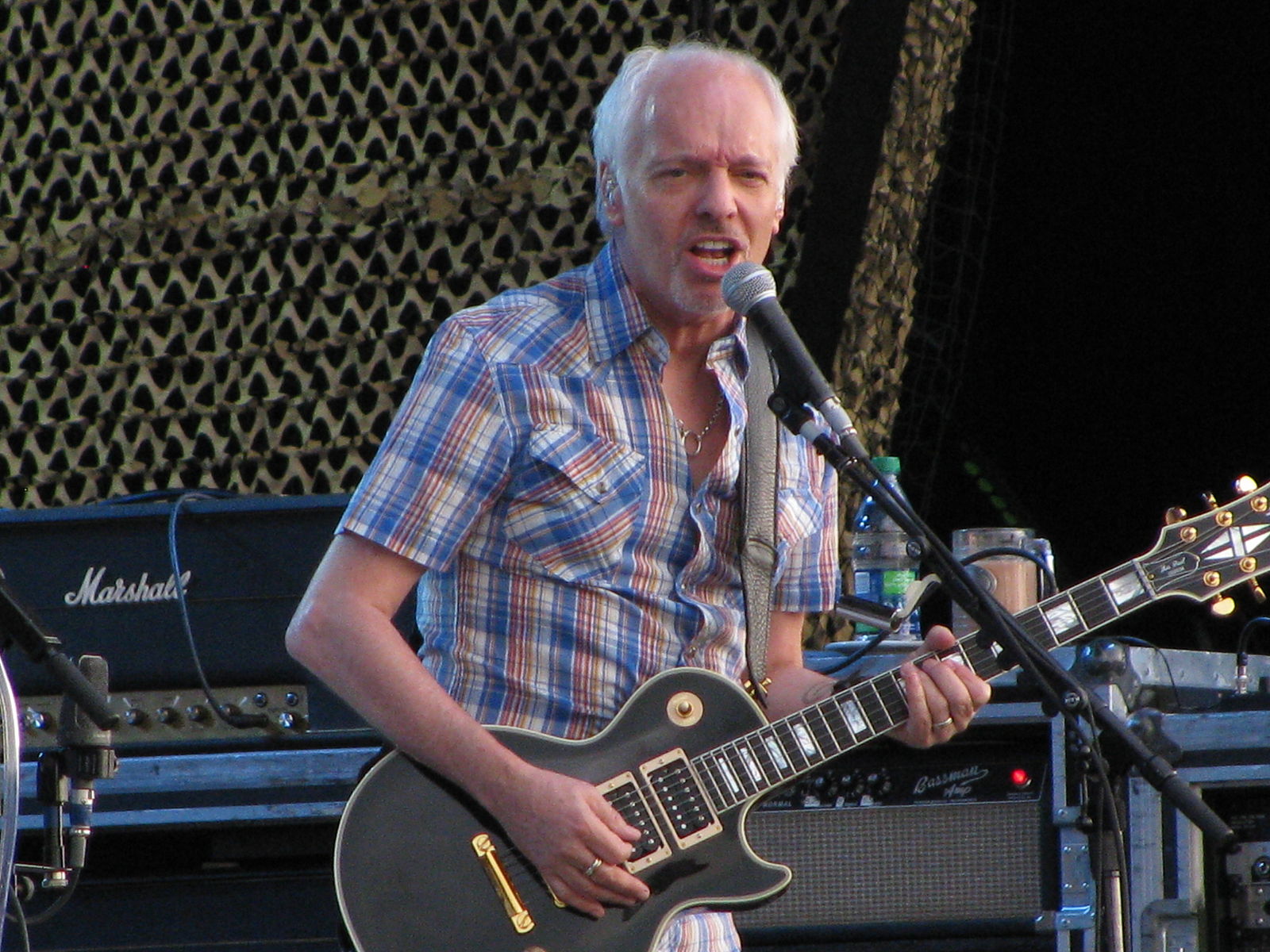

(header photo courtesy David Morris Songer)

By Steve Houk

There are three words that most accurately sum up my high school years in the late ‘70’s.

Not “the big play.”

Not “the senior prom.”

Not even “the back seat.” Although it sure was fun back there.

No, the three words that bring back the most treasured and nostalgic memories from those formative years are: “Frampton…Comes…Alive.”

The British superstar’s momentous live album, released in 1976, is an infinitely symbolic soundtrack of those times for millions of us late-Boomers who grew up back in the post-Watergate years. For a lot of us, every song on the record is immensely evocative, and indicative of the spirit of the magical moments from way back when. When I play it now, I’m right back standing around the keg in Bob Funnell’s backyard junior year, or in the front seat of Johnny Kaz’s Dodge Dart, driving around the back roads of my home town, not a worry in the mind, or a care in the world, other than which party to go to. Yep, it brings it all back.

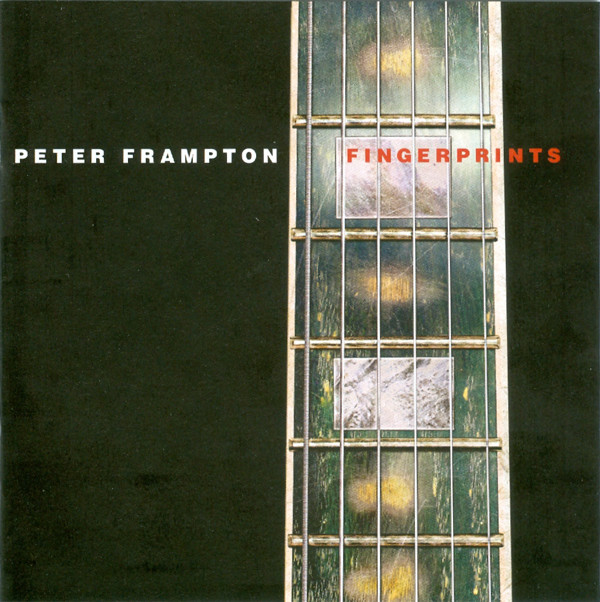

And thirty three years later, as Frampton Comes Alive sits as one of rock’s all-time top selling live albums with close to 20 million units sold, Peter Frampton is still yes, very alive, and very well, thank you. And he’s very happy to talk about things other than his landmark disc, which includes being invigorated by not only producing records for up and coming stars like Davy Knowles and Back Door Slam, but is also rooted in the reception for his brilliant instrumental record, “Fingerprints”, which won him a best Pop Instrumental Album Grammy in 2007.

“The fact that ‘Fingerprints’ has been accepted the way that it has, it’s made a huge change in my career for the better,” Frampton, 59, told me. “It definitely gives me the feeling of acceptance as the musician, finally. ‘Frampton Comes Alive’ is an amazing legacy that seems to still be barreling on from generation to generation, which I am absolutely over the moon about, but we can actually talk about something else. I’m not putting it down at all, it’s a wonderful thing, it’s just I’ve got ‘Fingerprints’ to talk about now, and it’s wonderful.”

What does Peter Frampton feel about receiving his first Grammy so many years after the staggering success of Frampton Comes Alive?

“Well in the end I’ve been nominated four times”, he said, “and most people probably thought I got one for ‘Comes Alive’, but the Eagles got it that year for Hotel California which was right. But you start thinking because you haven’t got one, ‘Well they don’t mean anything’, and then you get nominated for one, and they all of a sudden start meaning something. Overall, it’s an incredible feeling. I’m humbled by it, not only the fact that I got a Grammy, but what I got it for, which is for my musicianship, and that probably means more to me than anything. My wife told me ten years ago, wouldn’t it be funny that when you finally get a Grammy, it’s for an instrumental? And she was right. She knew what it meant to me, what guitar playing means to me. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t dislike anything that I do, I just have a passion for guitar playing, I always have, and to get overlooked in the onslaught of ‘Comes Alive’ was a bit of a downer, there was so much other good stuff going along for me at that point. So it might be 30-plus years later, but yeah, I’ll take it.”

“Fingerprints” is a brilliant showcase for Frampton’s exceptional guitar work, which has grown even stronger since the days of “Do You Feel Like We Do.” He lists some top-shelf rock players as collaborators on the record, including former and current Rolling Stones Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts, Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready and Matt Cameron, and Warren Haynes, the gifted singer/songwriter and guitar ace from the Allman Brothers and Government Mule. How did Frampton gather such A-List talent for the sessions? Maybe it’s simply because he is who he is.

“It was all pretty much by accident, and a wish list, obviously. I knew of Warren, and we’d met a couple of times just touring and stuff. I knew how wonderful he was, and I just asked him and he said yes, and then we set up the session. He said ‘Come in a day early to New York because I’m playing with the Allman Brothers, you know we’re doing our yearly 13 or 14 gigs straight’, and asked me to come sit in. At the time I didn’t realize he was the bandleader of the Allman Brothers. So I sat in with them and did two numbers, and it was amazing. I’ve been a huge fan of theirs since their inception, from the first time I heard ‘Live at the Fillmore.’ And then the following day in the studio, he and I continued the musical conversation.”

With Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready and Matt Cameron,” Frampton continues, “I knew Mike as a by product of doing (the film) ‘Almost Famous’, and then they invited me to play when we were trying to get rid of our President mid-term on the Vote For Change tour (Frampton has been an American citizen since shortly after 9/11). So I’m up on stage with Pearl Jam, Neil Young and Tim Robbins, and it was amazing. And that next day, I asked them to play on the record, and they said ‘Yeah, alright!’ We were only planning on doing one number, and then we did end up writing one too, and that was fantastic.”

Frampton’s grandmother could certainly get extra credit for helping jump start his illustrious lifelong career. He found a “banjolele”, a combination banjo and ukelele, in her attic when he was six. “I think there was a method to her madness, I think she gave it to Dad and stuck it in the attic and said that maybe one day the boys will pick this up. The funny thing is, we’d always go up to the attic, my brother and I would, to get the suitcases down for vacation, and the first year I said ‘What’s that?’ and we opened it up and looked at it, and we closed it and left it there. The second year when I was seven, I said ‘You know what, I think I’ll take that down, Dad.’ He showed me a few chords, and the next thing I knew I was playing ‘We’ll be comin’ round the mountain when they come’, you know.”

As for the mechanics of learning how to play, he endured early lessons only to get some of the basics honed that would help him later on. “I learned by ear, as they say, and then after I’d been playing for about four years, my parents decided that this was obviously serious, and they said that I had to go take classical guitar lessons, so that’s what I did for the next four years. I hated but loved it at the same time. I felt it was a waste at the time, I was not able to use that time to play Shadows numbers or Ventures numbers and rock and roll, but I realized afterwards that it gave me the fundamentals of the guitar and to be able to decipher on paper, printed music for guitar.”

Frampton had astounding musical company early on in grammar school, counting David Bowie as one of his early school mates, and jamming with the future Ziggy Stardust on covers in the school cafeteria. He was influenced by not only the likes of The Beatles, Cliff Richard and Buddy Holly, but also by Hank Marvin of The Shadows, who also plays on “Fingerprints”, as well as the brilliant gypsy jazz of Django Reinhardt, the latter thanks to his late father Owen. In fact, Frampton dedicated the entire “Fingerprints” record, and two moving odes on it, “Oh When” and “Memories of Our Fathers”, to the artistic man who quietly supported his growing success.

“My parents never guided me musically, they did only when I showed interest early on, and I was pretty good from the start, and they would be very encouraging, but not wishing to push me into the music business, which I did myself. But my father…he was an artist, a painter and an illustrator, he did just about everything, and I guess I got his work ethic. He never stopped, and I don’t ever stop. But there was something special about the way he would encourage me…it wasn’t really spoken, it was just something we had together. I did play him ‘Black Hole Sun’ (the Soundgarden cover for which Frampton was nominated for a 2007 Rock Instrumental Grammy), so he did get to hear it before he passed, and he said, ‘Well, that’s very different!’ He never heard the finished ‘Memories of Our Fathers’, which is the very last track we did on the record. It was a labor of love for my father, that was. When I went over to England for his funeral, “Oh When” is the piece I played. I ad-libbed the piece on guitar, it was just a little instrumental intro that I did at the funeral, and I remembered it and recreated it as soon as I got back to the States. In fact, I got back, cancelled the sessions at my house and on the following Monday, I came down and said ‘Just stick a mike up, I gotta go do this now’ and then I did three takes, and then said, “Let’s all go home, I can’t do any more.” I just was fresh off the plane basically from England, but I got that down in the spirit mentally that I was in at that point, so it’s very important to me, that track, even though it’s so short.”

As for what caused his epic 1976 live opus to gain a place in rock and roll history, Frampton says it’s all about the live vibe versus the studio one. “Live is the perfect forum for me. I just absolutely love it. I think Elton John said it best, he said, ‘You never know when it’s gonna be a great show.’ Elton said, ‘I have been so well rested, exercised, eaten well, got on stage that night…and it sucked. I just didn’t enjoy it, nothing happened right. And then other times I’ve had 103 fever, felt like cancelling the show, went on stage, and it was the best show I’ve ever done, or I’d done in like six months.’

“When you’re in the studio playing something to a pane of glass, with people behind it, you pour your heart out, and then at the end of the song, whether it’s a solo or a vocal or whatever, you go ‘So what do you think?’ and they say ‘Well, that’s good, let’s try it again’, it sort of takes the excitement from it. Live, there’s no take two, it’s always take one, and it’s always different, every show is so vastly different, every audience is different. I think that’s what I like about it the most, is that anything can happen. Whereas everything’s so planned in the studio. I like things off the cuff, as much as possible.”

Do you feel like I do? It’s guaranteed you will, Sept. 2nd at the sweet Birchmere.